Artificial Intelligence and Dispute Resolution: A Primer and Opportunity for the Future

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been progressing for a decade or more but its most recent achievements have thrust it into the spotlights. So what is it, and what could it mean for the dispute resolution profession?

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been progressing for a decade or more but its most recent achievements have thrust it into the spotlights. So what is it, and what could it mean for the dispute resolution profession?

First, AI refers to the use of computer processes that mimic the ways humans think. AI is particularly adept at finding patterns and correlations in very large data sets – far larger than humans could analyze. There are many subfields within AI, but the areas of greatest relevance to dispute resolution are large language models together with natural language processing (NLP), and emotion AI. This post will focus on large language models and NLP.

The computer uses a large language model and NLP to interpret voice or text inputs and respond. NLP technology has powered things like Alexa, Siri or Google Home and even basic internet searches in Google or other browsers for some time. The technology uses an enormous volume of examples of human communications as its input data – thus the name, large language model – which the NLP algorithms are trained on to identify patterns in the way humans respond. An NLP application can then choose the response with the greatest probability of reflecting what a human might have wanted done or said in response. The result is a kind of synthetic human communication augmented by access to vast amounts of information. Until recently, responses have been limited to a few words and reacting by performing a simple search or command.

Enter, ChatGPT…

ChatGPT, which exploded into the spotlight this year, represents an enormous next step in AI referred to as “generative AI” (the ‘G’ in ChatGPT stands for generative) which can create something completely new, not just perform a search or execute a command. The large language model’s vast quantity of human generated communications available on the internet – books, articles, blogs, social media, video and so on – have been processed into ChatGPT with limited or no categorization or curation for accuracy, social propriety or other characteristics.

This process is aptly named “unsupervised learning.” In contrast, doctors have used supervised learning by labeling historical patient records including mammograms as patients who developed breast cancer versus those who did not. An AI program then sought patterns within these known groups, and could apply this learning to diagnose new cases with impressive accuracy. The new generative AI using unsupervised learning has the ability to respond to a prompt by pulling from the sea of input data to create something entirely new. It can create images on request such as an urban landscape done in the style of Monet, or write a poem about anything, author a college term paper or draft software code. This is the next-generation capability that has caught everyone’s attention. It mimics human reasoning and communication with stunning accuracy and can also combine things in ways beyond human skills.

One prompts these tools providing context and using plain English language like, “Draft a blog post about how AI will affect dispute resolution and mediation.” Hit return, NLP takes over, and in less than a minute you’ll have a well-written product suitable for publication. The better the prompt, the better the answer. These chatbots are iterative, so you can read the bot’s response and prompt it to further refine the work product or even mimic a real conversation.

There have been reports of iterative conversations going wildly off the rails with the bot expressing human emotions or motivations, proving that the technology is still in its infancy. Its training using unsupervised learning may explain this occasional peculiar, emotional mimicry. Remember that this is a system that is simply computing probabilities for a response to the prompt based on the unsupervised consumption of online social media, fiction and nonfiction as well as more authoritative sources. If you provide it with emotion-laden prompts, it will do its best to respond based on its training data.

A tool to help mediators

AI will likely become a tool in the hands of a dispute resolution professional. There are some intriguing examples of current and near-term uses. Bing’s version of ChatGPT generated a reasonable draft settlement agreement based on a prompt containing only a few notes of agreed terms and the type of case. It made sentences out of the shorthand notes and incorporated some formal settlement boilerplate it determined was applicable. In response to a different prompt, it instantly offered a half-dozen legitimate tactics a mediator might use to break an impasse in negotiations, together with citations to the articles it pulled them from. It is not much of a leap to being able to generate a list of issues to be addressed in a case if given written position statements from the parties, or even to provide suggested compromises.

These are very modest, short-term uses based on the existing applications. For now, these tools pull from the vast ocean of disorganized, unlabeled content on the internet to assemble a response and may have limited relevance in very specific contexts like, say, divorce mediation. However, you can curate additional input data from within a specialty to further train these applications. This will improve their responses in a particular field or profession. For example, two years ago, an earlier version of ChatGPT was trained on call transcripts with troubled teenagers and could then convincingly play the role for use in training counselors in The Trevor Project, a hotline for LGBTQ youth.

Looking ahead

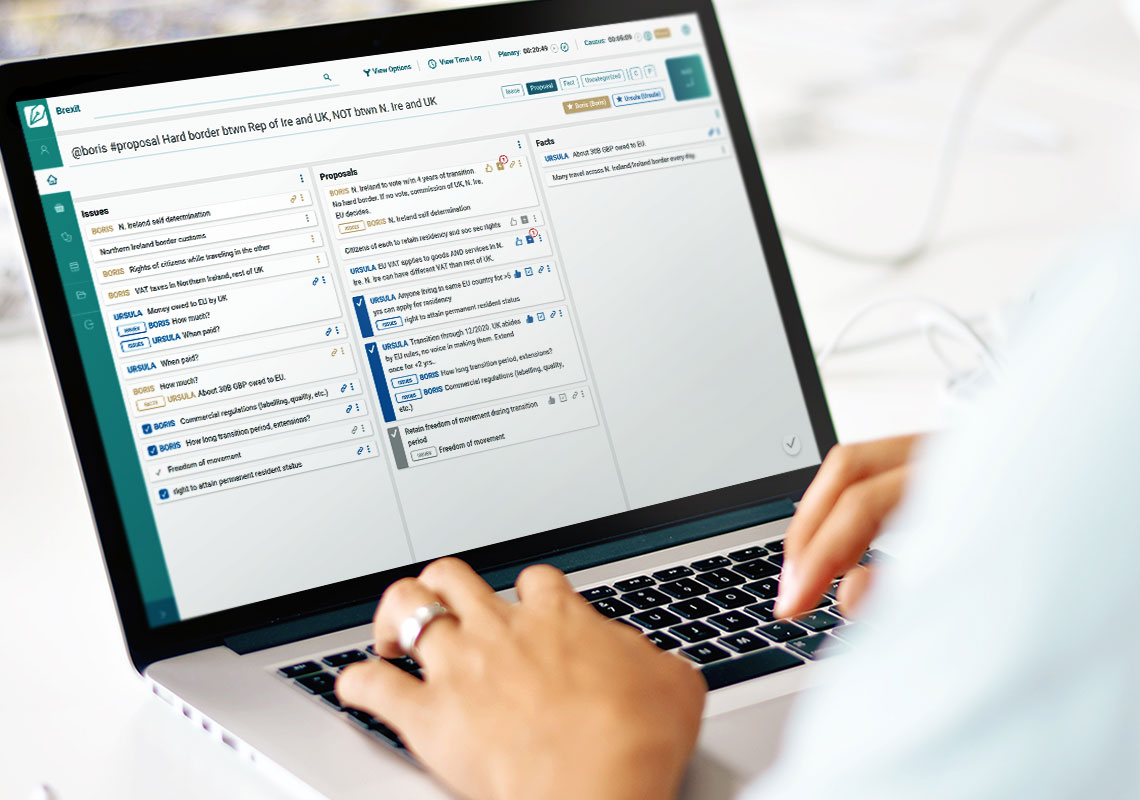

It is easy to imagine that with additional training inputs AI could take substantive, organized and categorized notes during a session, not a transcript, identifying issues, proposals and counterproposals or principles in real time – a true “digital assistant” – freeing the mediator to focus on the participants. With additional training AI will be able to suggest relevant, case-specific questions a mediator might explore and offer detailed, relevant proposals for the parties to consider, all provided in positive, optimistic language suited to the task.

For the foreseeable future, AI will serve as an assistant to the human mediator. Eventually, one can imagine co-mediating with an AI partner. But its reliability, consistency, and application to specific types of cases need to be developed and tested. The profession can use the time while it is just an assistant to the human to consider the ethical issues that will arise if or when the technology becomes a more active ‘fourth party’ at the table. It is a great moment in time for us to creatively consider how to adopt this exciting new technology in the manner most helpful to the objectives of mediation.

Gary Doernhoefer is the founder of ADR Notable, the Co-Chair of the ABA Dispute Resolution Section Technology Committee and a frequent presenter on the topic of technology and dispute resolution. ADR Notable is an easy-to-use case and practice management software platform designed specifically for the dispute resolution practitioner. Learn more at https://www.adrnotable.com.