Are Demographics Destiny for Technology in Mediation?

The age demographics of consumers of mediation services and mediators themselves will likely drive the adoption of technology to assist in the delivery of mediation services in the very near future. Clients will accept, or even expect, the use of common technology. As professionals move into mediation from careers in law or business they will be the first generation to have used technology from the earliest days of their careers and may expect to use similar tools in the practice of mediation. Technology providers must address this need by providing technology solutions that perform tasks computers do well while respecting where human skills are still essential.

Demography is destiny

The phrase “demography is destiny” is attributed to Auguste Comte, an early 19th century French sociologist often described as the father of positivism. The phrase is generally taken to mean that population trends often compel certain predictable impacts on society. Applying Comte’s observation, it seems very likely that key demographics of both mediators and their clients are about to usher in greater acceptance of technology in the delivery of dispute resolution services by mediators.

There has been a lot of talk about technology and dispute resolution in recent years. The topics vary from online dispute resolution (ODR) and the use of videoconferencing to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and sophisticated predictive analytics to facilitate settlements directly between parties. But progress has been slow, particularly when compared to the rapid adoption of technology in most other aspects of society. In their paper, “Mind the Gap: Bringing Technology to the Mediation Table” 2019 J. Disp. Resol. (2019) Alyson Carrel and Noam Ebner provide ample evidence of this failure to keep pace with the adoption of new technologies generally, and note the risks that arise for the profession as a result. The question is whether demographics of both parties to mediation and the mediators themselves will come to the rescue.

Evolving consumer demographic

First, it is obvious that the demographics of parties to mediation are changing. Carrel and Ebner point out that the Millennial generation already “comprise a significant portion of mediation parties today, and this will increase in the near future.” (Id. at p.20) They cite literature describing the relationship between Millennials and technology that we all recognize – instant communications, access to information at all times and the expectation of efficiency in the delivery of services. At a minimum, these attitudes will provide an acceptance of the use of technology by their service providers. And perhaps more. Millennials’ expectations may be that any professional service provider use technology and modern digital tools in the proper performance of their work. Not using well-accepted technology could lead to a loss of confidence in the service provider.

This suggests that we are on the cusp of a growing “pull” for technology from the consumer side of mediation. But what about the ability of the profession to respond?

The mediators

As a class, the age demographic of mediators skews older than most professions. Many mediators come to the practice after years in a different career. The Bureau of Labor Statistics observes, “Arbitrators, mediators, and conciliators are usually lawyers, retired judges, or business professionals with expertise in a particular field, such as construction, finance, or insurance. They need to have knowledge of that industry and be able to relate well to people from different cultures and backgrounds.” (Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While demographic data specific to mediators is hard to find, FINRA, the government-authorized watchdog for investment broker-dealer and related financial transactions, manages an alternative dispute resolution program and reports demographic data on its roster of neutrals. In 2019, only 19 percent of the mediators on their roster were age 60 or less. (FINRA) This data is likely to overstate the higher age demographic generally because it lacks representation of younger mediators practicing in other fields like family law where direct entry as a mediator is more likely than in the specialty of financial regulation. While this skewing toward the high end of the age range may make the FINRA data a slightly extreme case, it is consistent with anecdotal evidence from an executive at one of the larger firms that offers an extensive panel of mediators.

Statistics like these suggest that many mediators have a great deal of professional experience, and that they may have worked for years before the widespread availability of personal computers. While nothing prevents the adoption of the right technology at any age, we can all recognize the very human, natural affinity for old habits that have served well for many years. The combination of the age data on mediators with this natural resistance to change wouldn’t seem to bode well for the adoption of new technology any time soon. But two additional data points offer greater optimism.

The key shift

First, the FINRA data, to the extent it provides a reasonable, or even slightly higher, proxy for the demographic profile of mediators generally, also notes that 50 percent of those joining FINRA’s roster of mediators in the twelve months leading up to October 2019 were age 60 or younger. Here is the key demographic shift: unlike their predecessors, these newly-minted mediators almost certainly used a computer and other technology throughout their careers prior to joining the FINRA panel. There is a wonderful anecdote to highlight this changing of the guard in Tools and Weapons, The Promise and the Peril of the Digital Age, by Brad Smith, the President of Microsoft. Mr. Smith turned 61 in January of this year, and describes his early adoption of technology while still in law school:

“I had bought my first computer the preceding fall at a time when, for most people, the devices were still uncommon. … Compared to a pen and paper or the typewriter I had used in college, word processing was like magic. Not only could I write faster, I could write better.” Building the habit in law school, he buys a new PC to take to his first job as a judicial clerk in 1985. The point is that nearly everyone 60 and younger has likely used a computer from an early point in their professional lives. As they shift to the profession of dispute resolution, they will bring with them a familiarity with the use of technology. The use of a computer and various technologies it enables will be part of the old habits to which they are inclined. After that, it’s just a matter of picking up new applications, tools or software, not nearly as big a step as ending manual processes in favor of the use of computers. Indeed, professionals just now making the shift to dispute resolution might reasonably arrive asking, “where’s the app for this?” fully expecting to use an appropriate digital tool designed for mediators.

The developers

There is one more important participant in the adoption of new digital tools by the mediation industry – those who develop and provide the technology. It will be essential that the technology offered to the mediation profession be genuinely beneficial to the practice. Brad Smith underscores this lesson as his story continues. Having purchased a new PC for his new job as a judicial clerk he goes on to say, “The judge for whom I worked was seventy-two years old at the time, and the office with my desk was filled with shelves of well-organized boxes containing his meticulous handwritten notes from more than two decades of trials and cases. … My arrival with a personal computer raised some eyebrows. That’s when I first realized the importance of using my computer to do what I needed to do better – writing memos and drafting legal decisions – without upsetting old practices that still worked well. It’s a valuable lesson that I take with me to this day: Use technology to improve what can be improved while respecting what works well already.”

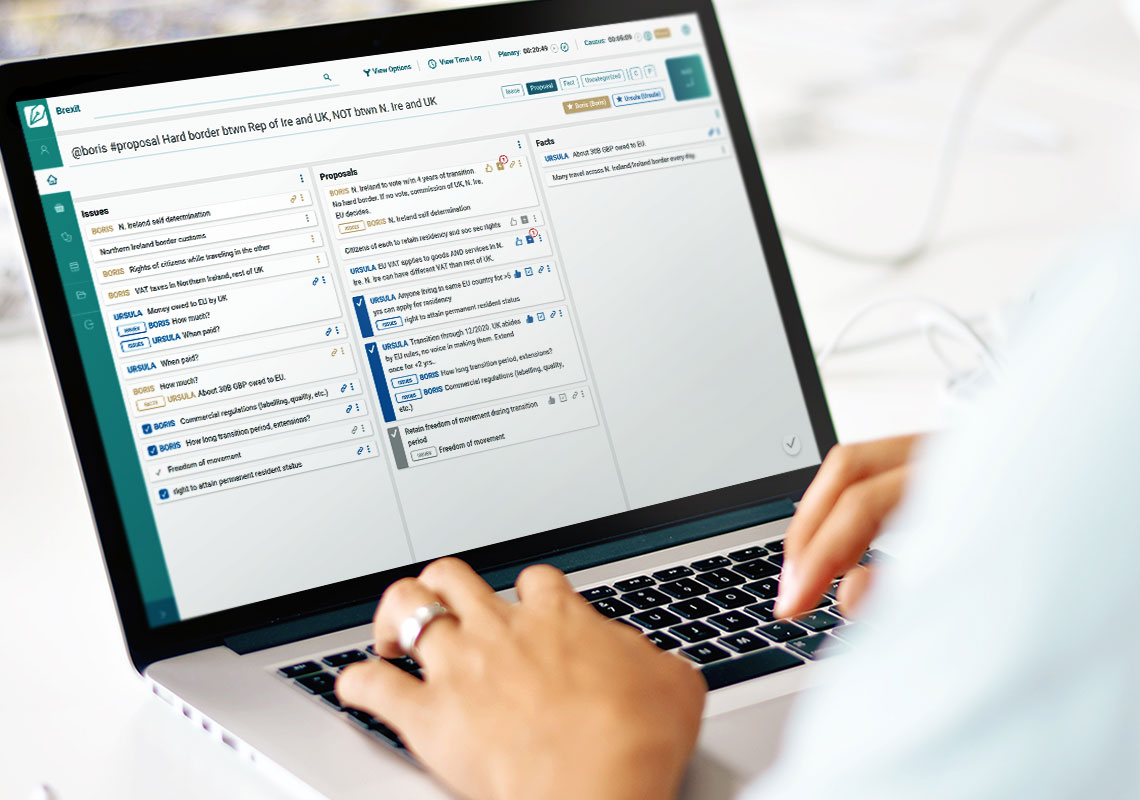

Now is the time. As the pressure grows for greater automation, pulled by clients and sought by a new generation of professionals, mediators and technology providers must form a partnership to identify, in the context of mediation, those things technology does well, and recognize those things it does not. Current, common technology is good at managing processes; recordkeeping, including rapidly finding and accessing information; flexible organization and visual display of information; word processing; electronic transfer of data, voice and video; and compilation of data or statistics. Humans skills are still essential for complex interpersonal communications, application of social norms and values, empathy, persuasion and consensus building, and creativity. For this industry to adopt automation it must be a tool in the hands of mediators that respects what has worked, helps them to be more easily organized, prepared and efficient, and relieves them of the tasks computers do well. We can respect what has worked in the past by ensuring the new technology reflects past manual methods in its user interfaces and organization. The goal should be a comfortable shift to such technology that allows mediators greater opportunity to apply their uniquely human skills in the service of their clients and helps the industry to catch up with the pace of technological change. That’s destiny for you.

Originally posted on Mediate.com