Scaling Mediation Skills to Address Community Discord

“STRENGTHENING COMMUNITY EFFORTS TO TRANSFORM DIVISION INTO ACTION.”

– The Divided Communities Project at Moritz College of Law.

Watching the demonstrations and protests across our country can be uncomfortable. You can agree that the underlying issues of race and inequality desperately need to be addressed with widespread, meaningful change. At the same time, you can also wish that discussion could have been catalyzed by something other than someone’s tragic death and that serious, deliberate change could take hold without further violence. In this, the protests that have swept our nation are like a fever. A fever is the body’s way of combating something malevolent, some underlying infection, while the protests are a society’s way of attacking something socially malevolent – prejudice. In both cases though, you wish there was a less painful way to affect a cure.

What can be done is to treat the symptoms and help the body heal. Doctors do this for their feverish patients, applying skills, knowledge and modern medical science. Something similar can be done in our society, by leaders with the skills to listen to competing points of view, empathize, clarify, build trust, find common ground, develop consensus around shared goals, and eventually gain agreement on tactics to achieve them. These leaders are likely to come from the ranks of mediation and dispute resolution professionals.

Micro and Macro Mediation

Mediators practice exactly these essential skills in the “micro” world, helping individuals or small groups find solutions to disputes with other small groups or individuals. The kind of leadership needed now brings these same skills into the “macro” social context instead.

The macro application of mediator skills often means focusing on teaching those skills to local leaders rather than applying them directly. The goal is less to solve a single dispute than to impart communication techniques that the local leadership can use to address discordant parts of the community on an ongoing basis. There is a wonderful example of this in the book, “Stories Mediators Tell, World Edition” edited by Lela Love and Glen Parker. (A terrific book if you haven’t yet acquired a copy.) In Chapter 22, “Training Day and Bag of Balls,” mediator Brad Heckman tells of working with the Roma people, commonly known as Gypsies, an ethnic minority often mistreated in the communities where they reside in groups. He recounts assisting a local facilitator in a small community in Slovakia where the Roma experienced the sadly typical range of prejudices from the local residents. His colleague, whom he calls Bolek, began by seating the participants in integrated small groups at a number of tables, leading to palpable discomfort among the participants. Then, directed by Bolek, Heckman distributed a huge variety of balls – tennis, ping-pong, bouncy ‘superballs,’ toy balls with faces or planets painted on them, bocce balls, marbles, baseballs, American footballs, and more – around the tables. The energy went from uncomfortable to playful as the participants refocused on the balls, not on each other. After a few minutes of silliness, Bolek asked each table to decide which, among the variety of balls, is the best. After 10 minutes, all of the tables failed to reach agreement. He then refocused the challenge, asking the participants at each table to decide what criteria might be used to determine the ‘best’ ball. They began to function collaboratively and developed reasonable criteria that might determine a ‘best’ ball. Having broken the ice, proven they could collaborate, and shown the advantages of agreeing on objective criteria in dispute resolution, he then asked them to identify criteria that could be used to identify the problems perceived in their community. They were able to agree on shared interests in safety, hygiene, education and housing, for a start. Heckman concedes they were still a long way from agreement on how to address these themes, but concludes, “the groups at least agreed on what to talk about, and, equally important, they were actually talking.” The macro application of basic principles right out of “Getting to Yes” had been infused into the local leadership for their ongoing use.

The Bridge Initiative

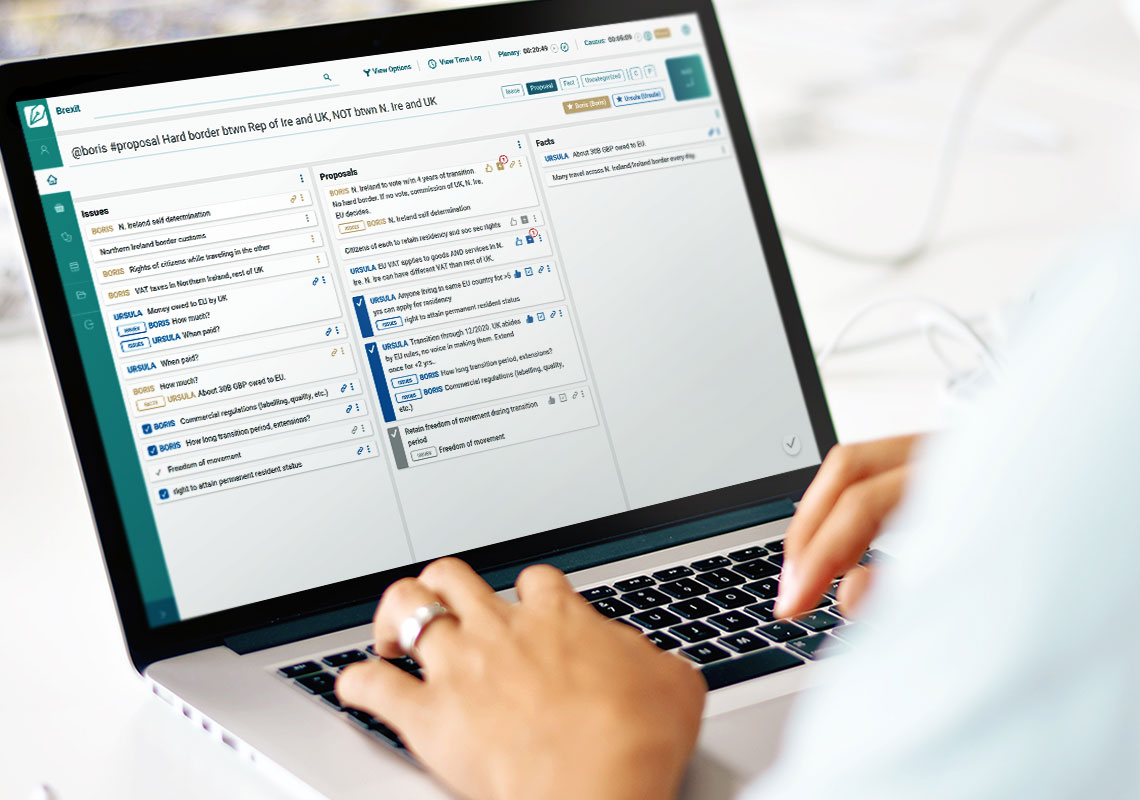

This approach has been the focus of the Divided Communities Project at the Moritz College of Law at the Ohio State University. One of its key initiatives, called The Bridge Initiative @ Moritz, captures the macro application of mediation skills perfectly:

“Across the country, local government, law enforcement, and community leaders are grappling with increasing tensions associated with hate incidents and crimes, officer involved shootings, and other incidents that have a lasting impact on individuals as well as entire communities. These local government and community leaders understand better than anyone the needs of their communities and share a sense of urgency to respond productively to civil unrest. And it is precisely in these times of crisis when the expertise of a mediator with experience developing processes that not only keep initial protests safe, but also offer a path towards engaging the entire community in realizing more systemic reform, is most valuable.”

The Bridge Initiative offers both mediation services and training in the skills and techniques desperately needed in communities where tensions – fevers – are running high. Just as the body rids itself of the infection if given care and assistance by a physician, mediators can help a community heal by providing members of the community with tools, techniques and skills (and maybe a bag of balls) that quell the symptoms and help the community find resilient, long-term health. These mediators are not likely to bring with them easy answers that address the community’s issues. Instead, they offer expertise in processes, means and methodologies that have been proven to help lead communities to their own cures. They have found that when well-intentioned, determined leaders in a community combine their intimate understanding of the values, goals and aspirations of the community with the listening, communication and processes of mediation, great change is possible.